Introduction to I Ching(Yijing): Ancient Wisdom for Modern Times

Explore the fundamental concepts, historical background, and practical applications of the I Ching in contemporary life

The tapestry of Chinese civilization is woven with threads of extraordinary depth and antiquity, but perhaps no single text holds a more central and foundational place than the I Ching (or Yijing). Known in the West as The Book of Changes, this venerable classic is not merely an antique artifact; it is, quite literally, the philosophical core from which much of Chinese thought, cosmology, and culture has sprung.

A Legacy Spanning Three Millennia

The origins of the I Ching stretch back at least 3,000 years, placing it among the most ancient surviving texts in the world. Its enduring legacy is a testament to the remarkable continuity of Chinese culture, a civilization that, unlike many others, has never suffered a complete break, allowing its most profound written works to be studied and appreciated across millennia.

While its true genesis is shrouded in the mist of legend, including tales of mythical figures like Fuxi, a materialist perspective suggests that the I Ching is the culmination of observations and accumulated wisdom of ancient Chinese sages. These early philosophers meticulously studied the celestial movements, the patterns of nature, and the dynamics of human society to formulate a cohesive theory of the universe. Fundamentally, the I Ching is a profound philosophical treatise a grand attempt to map the origins and constant flux of the cosmos.

The Essence of "Change"

The very character Yi (Yi, 易) in Yijing encapsulates its central theme: change or transformation. The book is a sophisticated exploration of how everything in the universe is in a perpetual state of dynamic evolution.

According to its deep cosmology, the universe began from Wu (无, or Nothingness). This nothingness gave rise to You (有, or Being), a singular, undifferentiated, and chaotic state much like the primal conditions before a cosmic "big bang," where all things were mingled without distinction.

From this primordial state of You emerged the fundamental duality that governs all existence: Yin and Yang (阴 and 阳).

This is the moment of differentiation and opposition. Just as the entire digital world can be built upon the binary code of 0 and 1, the I Ching uses the relationship between Yin and Yang to model the entire universe, capturing the essence of countless dualities:

| Polarity | Yang (阳) | Yin (阴) |

|---|---|---|

| Symbol | —— (Solid Line) | -- -- (Broken Line) |

| Numerical Value | Nine | Six |

| Concept | Masculine, Hard, Active, Heaven, Creative, Positive | Feminine, Soft, Passive, Earth, Receptive, Submissive |

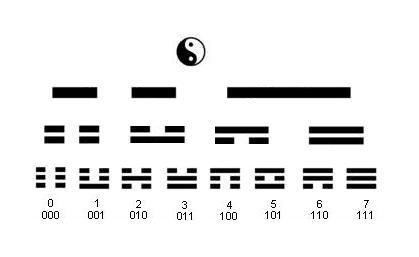

The fundamental unit of the I Ching is the Yao (爻), or line, which is either Yang (a solid line) or Yin (a broken line).

Core Concepts of the I Ching Philosophy

The philosophical insights within the I Ching are vast, but they revolve around several interlocking concepts that define the Chinese worldview.

1. The Dynamic Interplay of Yin and Yang

Crucially, the I Ching does not view Yin and Yang as static, separate forces of 'good' and 'evil,' but as mutually dependent, interpenetrating, and constantly transforming energies:

- Mutual Dependence: One cannot exist without the other; they are conditions for each other's existence (e.g., you cannot know 'up' without knowing 'down').

- Interpenetration: Each contains the seed of the other (the famous white dot in the black half of the Tai Ji Tu).

- Waxing and Waning: They are in a continuous, cyclical state of ci xiao bi zhang (此消彼长), where one recedes as the other advances, and vice versa.

This dynamic interaction is perfectly visualized by the Tai Ji Tu (太极图), the Supreme Ultimate Diagram, a circle divided by a continuous S-curve, illustrating the harmony of their balance and constant motion.

This fundamental law of dynamic equilibrium leads to one of the most important principles in Chinese philosophy: "When things reach an extreme, they reverse" (物极必反). For instance, a period of extreme prosperity and excess will inevitably sow the seeds of its own decline, just as the deepest winter contains the subtle promise of the coming spring. The moment the Yang energy peaks, Yin begins to grow, ensuring perpetual motion and change.

2. From Duality to Complexity: The Evolution of States

The continuous motion and combination of Yin and Yang naturally produce higher-order structures: the Four Images and the Eight Trigrams.

The Four Images (Si Xiang)

By combining two Yao lines, four possible configurations emerge, representing the four essential stages of the Yin/Yang cycle:

- Tai Yang (太阳, Greater Yang): Both lines are solid (full Yang).

- Shao Yang (少阳, Lesser Yang): The lower line is Yin, the upper is Yang (rising Yang).

- Tai Yin (太阴, Greater Yin): Both lines are broken (full Yin).

- Shao Yin (少阴, Lesser Yin): The lower line is Yang, the upper is Yin (rising Yin).

These stages describe the transitional phases found in seasons, life cycles, and the development of any phenomenon.

The Eight Trigrams (Ba Gua)

The Ba Gua (八卦) are formed by combining three Yao lines, yielding eight fundamental Primary Trigrams, each named and associated with a core concept, a natural phenomenon, and a direction.

| Chinese Name | Trigram Symbol | Associated Concept |

|---|---|---|

| Qian (乾) | ☰ | Heaven, Creative Power |

| Kun (坤) | ☷ | Earth, Receptive Power |

| Zhen (震) | ☳ | Thunder, Arousing |

| Xun (巽) | ☴ | Wind/Wood, Gentle Penetration |

| Kan (坎) | ☵ | Water/Abysmal, Peril |

| Li (离) | ☲ | Fire, Clarity |

| Gen (艮) | ☶ | Mountain, Resting |

| Dui (兑) | ☱ | Lake/Marsh, Joyous |

The Sixty-Four Hexagrams (Liushisi Gua)

The final, most complex structure is the Sixty-Four Hexagrams. These are created by combining any two of the Eight Trigrams (an upper and a lower trigram), resulting in 8 × 8 = 64 unique six-line figures. Each of the 64 Hexagrams has a specific name, image, and detailed commentary, representing a distinct type of situation, a phase of development, or a state of interaction in the world. The six lines within a Hexagram are read from bottom to top, representing the different, sequential stages of an event's unfolding, from its nascent start to its culmination.

The developmental pathway of the I Ching's cosmology can be summarized elegantly:

Nothingness (Wu) → Being (You) → Yin and Yang → Four Images → Eight Trigrams → Sixty-Four Hexagrams

This cosmological journey is beautifully echoed in the Tao Te Ching, written by Lao Zi over 2,500 years ago, which often serves as a commentary on the principles of the I Ching:

Return is how the Way(Tao) moves. Weakness is how the Way(Tao) works. (Chapter 40)

The Way(Tao) gives birth to the One (the undifferentiated You). The One gives birth to the Two (Yin and Yang). The Two gives birth to the Three (the combination of Yin and Yang). The Three gives birth to the ten thousand things. (Chapter 42)

3. The Grand Principle of the Unity of Heaven and Humanity (Tian Ren He Yi)

Since the I Ching is a model of the most fundamental principles of change, it posits that the same laws govern the entire cosmos from the grand movements of the heavens to the smallest details of life. In this philosophical system, everything from natural phenomena and the functioning of the human body to the evolution of society can be described using Yin/Yang and the patterns of the Hexagrams.

This insight gives rise to the profound Chinese philosophical tenet of Tian Ren He Yi (天人合一), the "Unity of Heaven and Humanity." It suggests that human existence is not separate from nature but integral to it. Therefore, ethical and practical actions should align with the universal, cosmic patterns of change and transformation.

Modern Relevance and Applications

Despite its antiquity, the I Ching is far from an obsolete text; its wisdom remains deeply relevant today.

Guidance for Life

The philosophy provides a timeless guide for navigating the complexities of existence:

- Cycles of Fortune: The idea of Fou Ji Tai Lai (否极泰来), meaning "after extreme difficulty, good fortune follows," offers a comforting reminder that misfortune is a phase, not a permanent state, and that life's cycles are ever-repeating.

- Collective Unconscious: The 64 archetypal situations described by the Hexagrams resonate so deeply that some have linked them to the concept of the "Collective Unconscious," suggesting they map fundamental human experiences.

Divination and Prognostication

For millennia, the most popular application of the I Ching has been divination (or prognostication). Based on the premise that human events are subject to the same cosmic rules as the rest of the universe, a specific Hexagram can be consulted using chance procedures (traditionally yarrow stalks, now often coins). The resulting Hexagram is interpreted as a snapshot of the current situation and the trajectory of its future development, offering guidance on how to act in alignment with the Dao (道) or the natural flow of events.

Ultimately, the I Ching is an invitation to understand that the only constant in the universe is change itself. It teaches us to observe the patterns, embrace the flux of Yin and Yang, and seek harmony with the eternal rhythms of the cosmos. It is a profound guide to living wisely in a world of constant transformation.